State and local authorities are preparing for massive flooding of the Tulare Lake Basin.

Record amounts of snow blanket the watershed, and now a record spring runoff is being driven by a wave of unseasonably high temperatures. Officials – bearing the worst-case scenarios in mind – are imagining valley cities around the lake flooding, and distant mountain communities becoming further isolated as the spring waters rise. Here is a look at what we can expect.

If Worse Comes to Worst

Though it’s only mid-May, summer-level heat has arrived early in the Central Valley. Already, temperatures are climbing daily into the high-90s, and the National Weather Service forecast shows nothing but more of the same.

Meanwhile, in the Southern Sierra Nevada sits the largest snowfall ever recorded there. It’s a whopping 437% of average. And now it’s melting. Forecasts for the area near Lodgepole at 6,700 feet in Sequoia National Park show nighttime temperatures never dipping below 36 degrees for at least the next week.

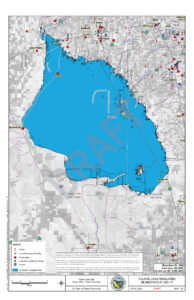

With that in mind, local authorities are preparing for flooding that could see – if the worst happens – the Tulare Lake fill with nearly 6 million acre feet of water covering more than 430,000 acres, or roughly 670 square miles.

Corcoran, Wakena, Stratford, most of Allensworth and at least the west side of Lemoore would be entirely underwater. Residents of Kettleman City may find themselves living on the edge of an inland sea that covers parts of Highway 41. Much of Alpaugh will also be submerged, but parts of it will sit atop the Tulare Lake’s only island, in the southeast reach just north of the Tulare-Kern border.

How quickly floodwaters will arrive and how severe flooding may be cannot be predicted. But, the state’s Department of Water Resources (DWR) says local authorities should prepare for a struggle that will last for months.

“This year, the Southern Sierra snowpack levels are similar to those in 1969 and have exceeded levels seen in 1983,” the DWR said. “This means flood impacts in the Tulare Lake Basin are expected to continue now through the summer, and as the Southern Sierra snowpack melts, is expected to result in sustained high-water flows until July.”

‘One of the Three Wettest Years on Record’

Currently, California has a snowpack with about three times the water content of an average year. Skewing that average to that extreme is the Tulare Lake Basin watershed here in the Southern Sierra. It carries most of the load at 437% of average snowpack.

While this presents a tremendous amount of water – equivalent to 39.2 inches of rainfall – the lake basin could contain it. At least it could if Tulare County (along with the rest of the Western US) hadn’t seen nearly unceasing rains for three months. Tulare Lake already covers thousands of acres and is growing continuously.

Ross Miller, chief engineer for the Tulare County Resource Management Agency (RMA), described the current situation.

“We are in one of the three wettest water years on record,” he said. Other record rainfall years were 1969 and 1983. “We are at a total of about 51 and a half inches for the Tulare Lake basin region – which is one of the hydrologic regions the Department of Water Resources breaks the state up into – it includes all of Tulare County as well as much of our surrounding counties.”

He described the inundating effects of the greater-than-normal rainfall in the Valley and foothills areas starting on December 26.

“To date we’ve received about twice as much water as an average year, a little less than that,” Miller said. “And in terms of reservoir storage right now, most of our local reservoirs are slightly encroached, which means they have a little more water than they are supposed to have at this time of year and they are into the space that is intended for flood control purposes.”

This means when spring runoff is at its greatest, the four reservoirs on the Kings, Kaweah, Tule and Kern rivers may not be able to contain the overflow.

Winter Storms Wreaked Havoc

The first round of serious storms to strike California arrived the day after Christmas and lasted through most of January. The excessive rain caused what Miller called “some interesting flooding impacts” across the county, notably overflowing creeks and waterways washing out bridges and roadways, along with localized flooding, especially in the Strathmore area.

“All of this led to some communities being isolated for a few days or up to a few weeks during that period,” Miller said.

Small neighborhoods along North Fork and South Fork drives in Three Rivers were cut off, as was Ponderosa, a village above Springville on storm-damaged Highway 190 between Sequoia National Forest and the Tule River Indian Reservation.

“Due to bridge washouts, the communities there were isolated for three to four days in Three Rivers, or for about two weeks in the Ponderosa area,” Miller said.

Though authorities couldn’t know it, the crisis was just beginning.

“And then March showed up,” Miller said. “The worst we saw in January was what we woke up to on March 10th, and from there we continued seeing impacts, new and developing, for another couple of weeks.”

The storms were so severe Lake Kaweah and Lake Success overflowed into their spillways. Unregulated water poured into the Valley’s waterways, many of which had seen little or no runoff for years. Mountain communities found themselves cut off again. On the Valley floor more than 70 levees and riverbanks – weakened by years of erosion and little maintenance – breached as the water rose.

The Damage Done

Hundreds of structures were damaged, including homes, businesses and ranches. Evacuation orders were issued. Mineral King Road, Mountain Road 99, Balch Park Road and Bear Creek Road all had major portions washed away, rendering them unpassable. More than a dozen bridges failed.

“We had 15 county bridges that were rendered impassable either because they were damaged or because they had washouts,” Miller said. “We are still working on providing emergency fixes for some of those.”

A complete list of roads that remain closed is available at the RMA’s website: tularecounty.ca.gov/rma/.

In the aftermath of the March storms, the RMA requested a state-led incident management team take over the emergency response. Dozens of state and federal agencies working in combination from headquarters at the Tulare International Ag Center took charge of the response. In all, 40 or 50 agencies, including the CHP, NWS and FEMA, became involved.

“A lot of things, I think, could have been a lot worse were it not for all of the great cooperation,” Miller said.

Emergency responders spend much of their time lining riversides and canal banks with miles of sandbags and temporary “muscle wall” levees. Airborne crews from Cal Fire and the sheriff’s department made food drops to those cut off by flood waters. They also took to the air with “supersacks,” oversized rock-filled bags dropped into breaches from above.

And they provided shelter for those displaced from their homes by the water. Refugees included people and their livestock.

“At times we had more animals than people in them, guinea pigs even, which always just made it interesting to find out what was in there on a daily basis,” Miller said.

Preparing for the Coming Meltwater

Near Allensworth, county crews raised a nearly 2-miles stretch of Avenue 56 to keep the tiny town open to its residents. It’s also a measure intended as a mitigation when flood waters rise again.

“This is so that should more flood water return to the area there is a specific way in and out of the community of Allensworth,” Miller said. “It will keep that community viable and in their houses for a much longer period, and is really just designed to protect for what will be coming this summer.”

What’s coming this summer is a lot of water. How it will arrive and when no one is certain. The only surety is most of it will end up sooner or later in Tulare Lake.

“The eventual size of the Tulare Lake will depend on many factors that remain uncertain including the amount of snowmelt runoff that is diverted before it reaches the lakebed for agricultural use and groundwater recharge, the timing of snowmelt, reservoir operations and other conditions,” said a statement from the DWR.

The DWR sent an 11-person team to Tulare County during the initial flooding to provide technical assistance. Along with hydrologists and flood-fighting specialists, the department also provided more than 200,000 sandbags and 17,000 supersacks to the area. Those specialists are also helping the county prepare for the deluge ahead.

“Beyond the current response efforts, DWR is looking ahead to help prepare the area for the coming snowmelt flood risk,” said Jeremy Arrich, Manager of DWR’s Division of Flood Management. “As the 2023 snowmelt season begins, DWR will continue to work closely with local county officials and US Army Corps of Engineers to determine what actions are necessary to protect public safety.”

In addition to continuing to supply technical assistance and resources, the DWR has also taken steps to ensure as much meltwater as possible can be used for recharging the area’s depleted underground aquifers.

State Covers Its Assets

Then on May 11, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed legislation to provide $290 million in relief for areas of the state impacted by flooding. Some $17.2 million of that cash will go toward bolstering the 14.5-mile levee that protects Corcoran.

This is the third time the state has stepped in to protect Corcoran from rising flood waters by raising the levee. Newsom hopes it will be the last. He expects local authorities to carry the ball from here on.

“Raising the Corcoran levee provides greater certainty that we won’t need to evacuate critical facilities and will ensure public safety,” a written statement from Newsom said. “However, the state and federal government cannot continue stepping in to raise this levee. I look forward to a conversation on what the local agency is going to do differently so that we don’t find ourselves in this situation again.”

The levee protecting Corcoran, along with the surrounding landscape, is slowly sinking as farms on the west side of the Valley used groundwater at unprecedented rates during the years-long drought ended by the rains of 2023.

Secured behind that levee are both the California State Prison at Corcoran and the California Substance Abuse Treatment Facility. Should flood waters inundate them, the state will be forced to relocate the population of prisoners, a costly, difficult and dangerous proposition.

Containing the Floodwaters

While banks of snow greater than most in living memory are trickling into runoff at an ever faster pace, flowing into the creeks and washes of the Southern Sierra Nevada, the RMA’s Miller is confident the water infrastructure will be able to handle the influx.

“Thankfully for Tulare County’s perspective, almost all of that snowpack is on one of our controlled watersheds,” Miller said. “So it’s either above Lake Isabella, above Lake Success, Lake Kaweah or Pine Flat (Lake), which means most of this will be controlled and will not come down in a way that we are expecting to see significant hazard.”

Still, he remains cautious.

“Not to say that there isn’t risk involved in this,” Miller said.

Attempting to wrangle this much water, while not an unprecedented task, is a feat almost no one working today in agriculture, irrigation management or state water regulation has faced before. But they’re willing to give it a shot.

“There’s a lot of effort being taken by the water masters on these rivers, by the Army Corps, by National Weather Service and Department of Water Resources to monitor what’s happening and try to make sure that as snowmelt occurs the reservoirs have adequate capacity and the rivers do not get in a situation where we are causing a new or different type of flooding than had been anticipated for the uncontrolled streams,” Miller said.

Among the resources compiled to prepare against the ongoing flooding is the Tulare Lake Atlas produced by the DWR. The atlas includes a series of 37 maps showing the extent of flooding in the lake basin depending on how much water reaches it.

A worst-case scenario would see the basin entirely flooded to the point the lake would overflow into an arm of the Kings River leading to the Mendota Pool. From there, the water would flow into the San Joaquin River Delta and eventually the Pacific Ocean. Miller said a flood of that size is “very unlikely to ever be anywhere close to realized.”

But it cannot be written off entirely, at least not yet.

“Unfortunately they (DWR) have not been able to complete their model yet to give us the sense of what actual pull elevation we are expecting,” Miller said.

We’ll just have to wait and see.