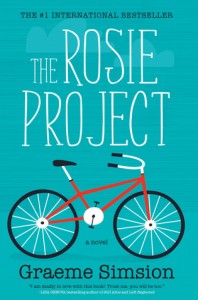

Graeme Simsion, author of The Rosie Project, writes with warm wit and comedic compassion. Simsion is also transparent in his intentions. Don clearly exhibits behaviors that fit the criteria for autism spectrum disorder, according to both common perceptions of the disorder and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the veritable bible of psychology. In the first few pages of the novel, Don voices that he believes those on the spectrum are inappropriately medicalized because their behaviors do not fit constructed social norms. Simsion uses the rest of his novel to make this case.

The comedic premise of this novel lies in our protagonist’s difficulties in understanding social norms. However, his differences can be quite advantageous at times: he is rational, honest and straightforward, which are useful attributes both in academia and with friends. He has a remarkable memory, and his attention to scientific and mechanical detail makes him an exceptional professor and researcher. In fact, Don’s life seems both enjoyable and fulfilling; the only change Don would like to make is adding a wife who is so logical and methodical as he. In this, Simsion brings to light a facet of living on the spectrum that many may not have considered before. It’s a misconception that those who have autism do not seek romantic connections and long-term relationships. It’s also easy for those who entertain this misconception to imagine that these supposed unattached lives are somehow less rewarding because of this. However, Don shows us that we cannot project our own ideas of fulfillment onto others’ lives.

Those who have built different lives are not to be pitied or judged. Don has few friends, but he enjoys his solitude, choosing how to spend his own time, and working within professional and personal systems that function best for him. He also does choose to seek love, though in a humorous and distinctive way. In this, Simsion argues that those with autism do not need to be medicalized because there’s nothing amiss about simple variations in human functioning, and that these differences simply reflect a larger range of social functioning than many constructed social norms allow.

It’s difficult to write characters who are different from many readers, especially characters who have real-life disorders. The author needs to make specific characteristics associated with the disorder clear, and the difficulties that arise due to them, but not create a stereotype. It’s likely most readers aren’t familiar with the medical criterion for autism spectrum disorder, so it’s important while reading The Rosie Project to remember that although many of Don’s traits are possible in someone on the spectrum, by no means does everyone on the spectrum embody each of these, and those who are not on the spectrum can share some of these tendencies as well. In short, these traits may be commonalities among certain people with autism – but in no way can they be ascribed to every person on the spectrum. Simsion avoids this potential pitfall by crafting Don as such a literary character that he reads purely as an imagined role, fit snugly into a fiction novel, so that it would be difficult for the reader to project Don’s personality onto actual acquaintances or friends.

However well Simsion has crafted Don, the author’s handling can feel clumsy at times. Don’s lack of self-awareness – he never seems to suspect that he may fall on the autism spectrum himself, although he discusses it in great length with other characters and even gives a lecture on the topic – seems unreasonable after 40 years of limited and difficult social interactions. Simsion also works hard to make Don’s likely diagnosis clear with a series of characteristics and behaviors that are typical of someone on the spectrum; however, Simsion includes so many of these signs that it feels at times as if he is working off a list, lacking either subtlety or trust in his readers to pick up on this important characteristic without spoon-feeding.

Another clumsy move Simsion makes is in his terminology. It’s true that the layperson is unlikely to catch this discrepancy. As someone with a degree in psychology, however, I would feel remiss to gloss over this misstep, although I do recognize its nitpicky quality. Simsion refers to Asperger’s Syndrome as the disorder that Don examines and likely has. The DSM V, the latest installment of the DSM, removed Asperger’s from their list of disorders in May of 2013. Instead of categorizing Asperger’s as a higher-functioning and separate form of autism, the DSM chose to integrate the two into one spectrum, called the autism spectrum. Throughout Rosie, Simsion refers to Asperger’s as a separate disorder, even though Rosie was published five months after the new categorization in the DSM. This categorization has been controversial for many reasons, and although those previously diagnosed with Asperger’s will retain their original diagnosis, the novel would do better, given its abundance of discourse on the topic, to address these issues instead of printing factually out-of-date information. Simsion’s argument revolves entirely around those living on the autism spectrum, and he would have done well to have used the contemporary language for this topic. His terminology is incorrect, but Simsion’s argument is nevertheless intact.

The only decisively unfortunate aspect of this novel is the ending. Up to this point the novel is a true romantic comedy: the focus is on humor with the romantic lead as merely a catalyst. The ending flips that modus operandi upside-down, turning the novel into a comedic romance. The last several pages emphasize not the soft bite of the earlier humor but a nearly saccharine romance. Yes, in a lighthearted novel, we should expect neatly wrapped details and for the guy to get the girl. But in a novel this witty, we should expect and receive an ending that is more realistic than sappy, more funny than cloying, and more truly romantic than sentimental. Don’s newly gained self-awareness is pleasurable and seemingly natural, but when it comes to

the summation, Simsion should have stuck with comedy. The last few pages detract from the charm that supported the whole of the novel, and without that charm, the last chapter falls flat.

Overall, Simsion navigates potentially tricky terrain with kindness and tact. Don’s social awkwardness does contribute to many moments of hilarity, but Simsion doesn’t make fun of his characters. At no point is the reader asked to laugh at Don instead of with Don. Simsion’s truly convincing argument is one of acceptance. Although the question of how autism is medicalized won’t be answered definitively in a novel, what we can all agree on is that it’s important to respond to Don and others like him with the same love, compassion, and patience that we would like to have from others. Don Tillman certainly would show this respect and kindness to any one of us.